RUDIMENTARY FIGURES

Rhoda Kellogg et al.

Aaron Garber-Maikovska

Ida Garber-Maikovska

Olin Garber-Maikovska

Sayre Gomez

Desi Eves Gomez

Isa Eves Gomez

Miranda Javid

Tala Madani

Christopher Richmond

Group exhibition curated by Jan Tumlir

January 10th - February 7th, 2026

Opening: January 10th, 2026, 6 - 9 PM

RUDIMENTARY FIGURES

Text by Jan Tumlir

What does a young child see when staring at a sheet of blank paper with a pencil or crayon in hand? Does it already appear as a surface fundamentally distinct from the tabletop that supports it? Is it sensed by the child as less a material thing than a space, a zone of opportunity? Might it even suggest a way out of the real and existing environment the child occupies? The table belongs to this latter space; its position was fixed long before. Like every other piece of furniture in the room, its presence is given. But then the paper might alight atop it as something more like a variable. Does the appearance of this pristine, white, rectangular, nearly weightless item somehow summon expression? And if so, what does it stand for in itself—a mere receptacle for impulsive marking or its instantiating ground and horizon of possibility? Perhaps the most daunting question we confront here pertains to those rudimentary figures that begin to appear right around age three: do these represent persons or else are they scribbles “personified”? One can only speculate.

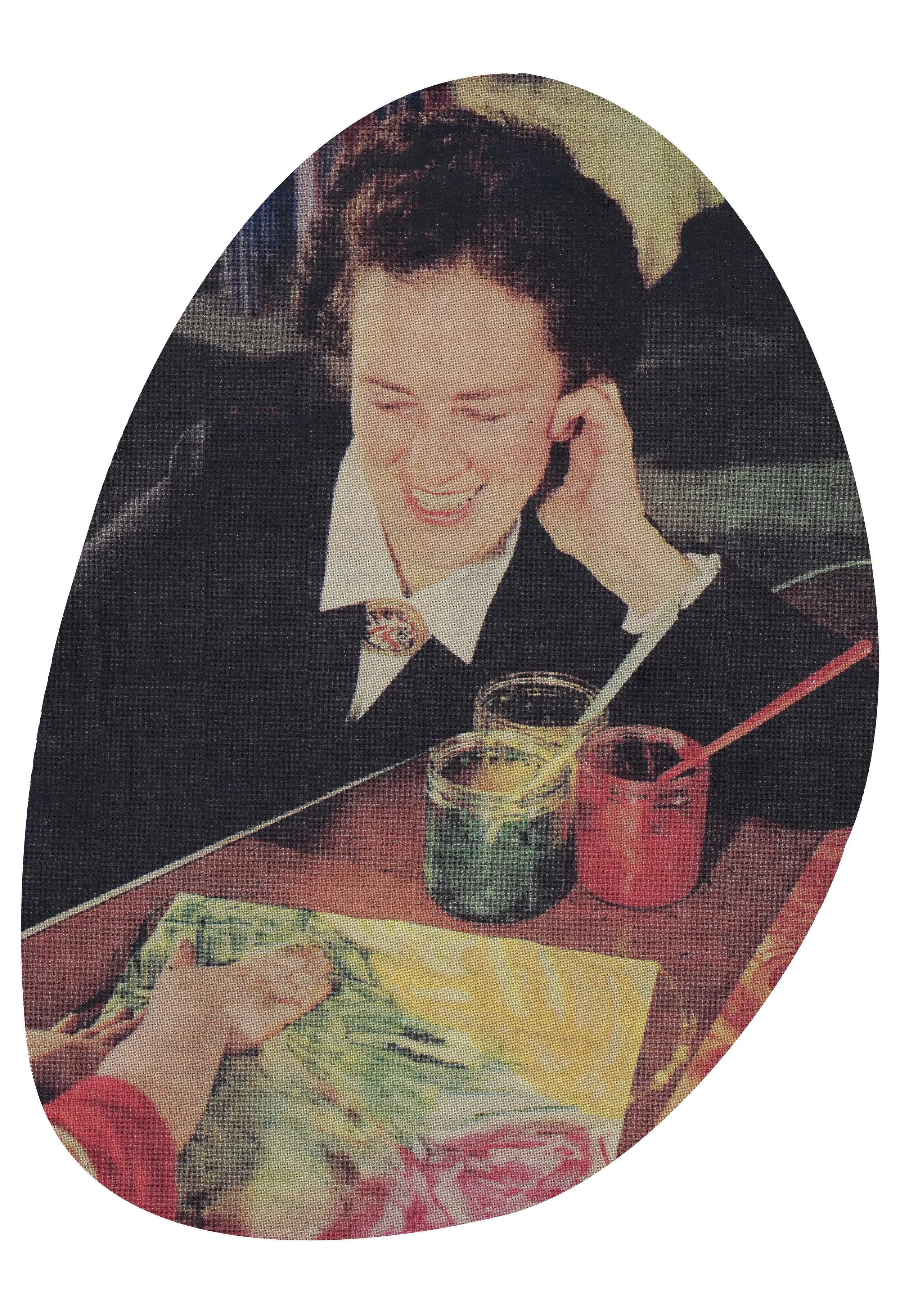

Yet such speculation can also be grounded in empirical observation of a child’s artmaking process. This exhibition is largely inspired by the work of Rhoda Kellogg (1898-1987), who did just that. Trained in child psychology, Kellogg operated as the director of the Phoebe A. Hearst Preschool Learning Center in San Francisco for nearly three decades beginning in 1945. Her experiences in the field were distilled into a series of books on children’s art, which remain no less insightful today than when they were published. “It has long been assumed that the primary pleasure young children derive from scribbling is that of movement, or ‘motor pleasure,’” she writes in Analyzing Children’s Art (1967), this being the set-up to a rebuttal that is central to her study: “It could equally well be assumed that visual pleasure is primary.” These words are the opening salvo of an exhortation to seriously consider the graphic output of children as bona-fide art. Kellogg was an avid collector of such art. A selection from her archive of over two million drawings by children between the ages of two and eight forms the centerpiece of Rudimentary Figures.

Kellogg came at her subject with empathy and admiration. This is an aptitude largely lacking in the statistically minded “experts” in child development that she spent a good part of her career disputing. The decision to view children’s drawings aesthetically above all—and, further, to delight in its forms—inures her against any charge of pseudo-science. In her estimation, these works should not be approached as indices of “excellence” or “lagging performance”; above all, they should not be corrected; no aspirational models were offered as a matter of principle. The guiding imperative of her study was hands-off observation. The pedagogical arguments derived from this practice were supported on a substructure of aesthetic philosophy, a discipline which does not trade in deliverables, which insistently detracts from any agreed-upon rule to swirl instead around the aporias of cognition—a “drunken whirl,” as Hegel puts it. We return to the start and push forward from there, thinking differently about the present and future as well. The point of departure is a blank page upon which a line begins to turn, scribbling.

The artists featured in Rudimentary Figures endow this scribble with very different temporal bearings: amongst the children, it is brand new—a line invented—whereas amongst the adults, it is age-old—a line returned to. Yet the aim of this exhibition is not so much to oppose as to feather-in these two perspectives. The result is a gradient scheme that resists any ideal of linear progression. Rather, at every point of exchange, there appears an inflection, a micro-crisis of control. A sense of gaining technical mastery is shadowed by that of its surrender. Archaism and futurity chase each other’s tails in children’s art, just as they do in art in general.

Art history supplies us with ample evidence of the fact that the perfection of form can lead to a dead end. Entire epochs have been plunged into a kind of creative stasis, yielding a succession of increasingly overwrought and reified products that admit no further movement except by way of breakdown, a back-to-basics turn. To apply that once-prevalent model of aesthetic development, “the ages of man,” we transition from youthful vigor to stiff senescence. But then there is always the possibility of a reversal. “The artist must live all the primitive experiments over again,” declares the art historian Henri Focillon near the end of his book The Life of Forms in Art. Published in 1942, this was a time when “primitivism” was very much on the avant-garde agenda. All the more so in the ensuing years—those of Kellogg’s most vital research—which also were marked by the ascendancy of Abstract Expressionism, Art Informel, Tachisme, the CoBrA and Gutaï groups, to name just a few of the then-reigning movements. Inspiration was sought equally in prehistoric art and the disjecta of contemporary culture. Markings on cave walls were correlated with urban graffiti, posters, stickers, and all sorts of crude imagery sourced from newspaper caricatures and comic books. Artistic “advancement” was sought through the back alleys of juvenilia.

None of this is over and done with. Even as our technologies of visualization rise to levels of resolution surpassing eyesight, many artists continue to favor an errant line, unbeholden to any logic of accuracy in representation. To this day, they follow the course set by the spontaneous markings of our ancient ancestors as well as the youngest among us. The drunken whirl of the scribble, which does not stay put on its surface or in its environment, is never wholly relinquished. Continually, it returns with the promise that the already made world—the table, the room, and all that surrounds it—can be left behind in favor of an emerging world. Motor pleasure and visual pleasure collide in those rudimentary figures that face reality rudely, as if to remind us that everything that constitutes the seemingly incontrovertible facts on the ground could still be remade “from scratch.”

______________________________________________________________________

Artists Bios:

Rhoda Kellogg

Rhoda Kellogg (b. 1898, Bruce, WI, d. 1987, San Francisco, CA) was an Early Childhood scholar, educator, theorist, author, and activist. She amassed an extensive and wide-ranging collection of child art through her travels around the world and through her work with children in numerous preschool programs, including Phoebe A. Hearst Preschool, which she designed and built. Over the course of six decades, Kellogg earned an international reputation for her pioneering research in early graphic expression through teaching, lecturing and publishing, notably in her books What Children Scribble and Why (1955), The Psychology of Children’s Art (1967), Analyzing Children’s Art (1969) in which she explains and documents her theories that children in all cultures follow the same graphic evolution in their drawing, from scribbles through certain basic forms, and that children’s art can be a key to understanding the mental growth and educational needs of children, and Children’s Drawings, Children’s Minds(1979).

Aaron Garber-Maikovska

Aaron Garber-Maikovska was born in Washington D.C., in 1978. He lives and works in Los Angeles, CA. Garber-Maikovska's work is in the permanent collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington D.C.; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris; Long Museum, Shanghai; Perez Art Museum, Miami

Ida Garber-Maikovska

Ida Garber-Maikovska is 9 years old and in fourth grade at The Willows Community School. Ida loves writing and collaging in her journal. She enjoys sketch comedy, directing her brother in improv, riding her bike and adventuring to old diners or scouting a track she’s never been on to run the mile.

Olin Garber-Maikovska

Ollin Garber-Maikovska is 7 years old and is in the first grade at The Willows Community School. He pitches left, bats right and wants to play for the Athletics when he grows up. Ollin loves board games, card games, dancing, and comic books.

Sayre Gomez

Sayre Gomez (b. 1982, Chicago) creates paintings and sculptures whose photorealistic virtuosity and scrupulous attention to detail reveal an unvarnished Los Angeles rarely seen in popular imagery. In their deep attunement to the incongruities and disparities visible on the streets of Los Angeles, Gomez’s immersive landscapes serve as local stand-ins for broader American realities. Abandoned cars, banal signage, neglected architecture, and other oft-overlooked corners become, through the artist’s “paint what you know” approach, vivid responses to class, race, and disenfranchisement. Even as they recall the hyperrealism of trompe l’oeil painting, his images resist strictly documentary readings. Originating in photographic sources that the artist crops, frames, and collages into composites, Gomez’s semi-fictional sites blur distinctions between the real and fabricated—appropriately in keeping with L.A.’s economies of fantasy. Both conceptually and materially, the artist’s practice—which also includes installation and video works—engages in direct dialogue with the enmeshed histories and attendant techniques of photography and painting. Subjects both minor and major—the minutiae of a trash heap and a sublime sky at dusk—are rendered to equally resonant effect through a rigorous process that includes photographing, digital drawing, projecting, stenciling, and ultimately, airbrushing. While the painted outcomes are, most immediately, powerful evocations of the contradictions of decline, so too are they records of their own time-intensive processes of becoming.

Gomez will be the subject of a 2026 solo exhibition at SITE Santa Fe in New Mexico. He has also presented solo exhibitions at Sifang Art Museum in Nanjing, China (2022–2023) and Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin, Italy (2022). Notable group exhibitions include The Life of Things, Museum Voorlinden, Wassenaar, Netherlands (2025); Fresh Window, Museum Tinguely, Basel, Switzerland (2024–2025); The Living End: Painting and Other Technologies, 1970–2020, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, IL (2024–2025); Ordinary People: Photorealism and the Work of Art since 1968, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA (2024–2025); Desire, Knowledge, and Hope (with Smog), The Broad, Los Angeles, CA (2024); PRESENT ’23: Building the Scantland Collection of the Columbus Museum of Art, Columbus Museum of Art, OH (2023); NGV Triennial 2023, NGV International, Melbourne, Australia (2023–2024); Changes, mumok, Vienna, Austria (2022–2023); and Dark Light: Realism in the Age of Post-Truths, Aïshti Foundation, Beirut, Lebanon (2022). Gomez lives and works in Los Angeles.

Desi Eves Gomez

Desi Eves Gomez is 6 years old and is in kindergarten at Dahlia Heights Elementary. Desi is an orange belt in karate at Benjanian Martial arts. In addition to karate, he loves animals (especially reptiles), trying new foods, painting, drawing, dancing, exploring the outdoors, and building robots.

Isa Eves Gomez

Isa Eves Gomez is 4.5 years old and is in T-K at Dahlia Heights Elementary where she was awarded star of the week. Isa is a ballerina studying at Bloom School of music and participated in two dance recitals last fall. In addition to ballet she loves to swing, sing, make art (especially with Play-Doh), dress-up and do her make up and nails. When she grows up, she would like to be an artist witch.

Miranda Javid

Miranda Javid (she/her) is an animator, curator, and art educator living in the Hudson Valley of New York State. Her films have shown nationally and internationally at festivals like the Ann Arbor Film Festival, Slamdance, Flatpack, Images, Eyeworks Film Festival, The Maryland Film Festival, and Animation Block Party. She is a former Kenan Fellow, Denniston Hill and Squeaky Wheel resident, a Sherman Fairchild grantee, and a recipient of the Nancy Harrigan Prize, given through the Baker Artist Fund. Her drawings have shown at The Baltimore Museum of Art, and The Mint Museum of Art in North Carolina. On her work, collaborator Brendan Sullivan once said, “Miranda’s work captures the pulsing network of the living, the heft of bodies, and the density of human experience. Her work is playful and somberly scientific, as it tracks time and decay with special attention to the body wading through it. There is a whole world in there, traces of the big unknowables, both the mystic and the muddled mess of human stuff. Within that unknowable mess, ritual is the mark left in time.”

Tala Madani

Tala Madani (b. 1981, Tehran, Iran) makes paintings and animations whose indelible images bring together wide-ranging modes of critique, prompting reflection on gender, political authority, and questions of who and what gets represented in art. Her work is populated by mostly naked, bald, middle-aged men engaged in acts that push their bodies to their limits. Bodily fluids and beams of light emerge from their orifices, generating metaphors for the tactile expressivity of paint. In Madani’s work, slapstick humor is inseparable from violence and creation is synonymous with destruction, reflecting a complex and gut-level vision of contemporary power imbalances of all kinds. Her approach to figuration combines the radical morphology of a modernist with a contemporary sense of sequencing, movement, and speed. Thus, her work finds some of its most powerful echoes in cartoons, cinema, and other popular durational forms.

Madani has been the subject of solo exhibitions at institutions including Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Seattle (2024); National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens, Greece (2024); Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA (2022–2023); Start Museum, Shanghai, China (2020); Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan (2019); Secession, Vienna, Austria (2019); Portikus, Frankfurt, Germany (2019); La Panacée, Montpellier, France (2017); MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge, MA (2016); Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, MO (2016); Nottingham Contemporary, England (2014); and Moderna Museet, Malmö and Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Sweden (2013). Madani’s work is in the permanent collections of institutions including Moderna Museet, Stockholm and Malmö, Sweden; Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA; Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, CA; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands; Tate Modern, London, England; Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan; and Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY. Madani lives and works in Los Angeles.

Christopher Richmond

Christopher Richmond makes videos, photographs, and drawings that interweave daily life with the imaginative realms of science fiction and myth. He received an MFA from the University of Southern California (USC) and a BFA in Film and Media Arts from Chapman University. Solo exhibitions of his work have been held in Los Angeles and Europe. His works are also included in the permanent collections of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Hammer Museum, and the Getty Research Institute. Richmond is represented by Moskowitz Bayse Gallery. He lives and works in Los Angeles.

Jan Tumlir

Jan Tumlir is an art-writer and teacher based in Los Angeles. He is a founding editor of the local art journal X-TRA and a long-time regular contributor to Artforum and Frieze. More recently, he has joined the editorial team at Effects, a London-based journal devoted to “aesthetics in the shadows of the contemporary." Tumlir has written extensively on such artists as Bas Jan Ader, Uta Barth, John Divola, Cyprien Gaillard, Allen Ruppersberg and James Welling. His books include: LA Artland, a survey of contemporary art in Los Angeles co-written with Chris Kraus and Jane McFadden (Black Dog Press, 2005); Hyenas Are…, a monograph on the work of Matthew Brannon (Mousse, 2011); The Magic Circle: On The Beatles, Pop Art, Art-Rock and Records (Onomatopee, 2015); and Conversations, produced in discussion with Jorge Pardo (Inventory Press, 2021). The Endless Line, book-length study of the role of gesture in painting, is forthcoming. Tumlir has served as a faculty member of the Fine Art and Humanities and Sciences departments at Art Center College of Design since 1999. In 2022, he joined the faculty of SCI-Arc as resident art historian.